The default implementation of the gRPC on .NET - Grpc.net is built on Grpc.Core which uses the protoc tool (see: ProtoCompilerOutput) to generate C# artifacts from .proto files. Also, it adds complexity to testing the services and sharing the contracts with clients. The proto files are artifacts/files shared between the clients and the server that need to be managed and kept synced between the two parties.

It is important to note that protobuf is simply a serialization format, and it is not dependent on proto files. We can significantly reduce our application’s complexity by removing the dependency on proto files and, thus, automatic code generation by the protoc tool from our application. A popular alternative to Grpc.net is protobuf-net.Grpc. The protobuf-net.Grpc library uses the code-first approach to declaring contracts. If your services are predominantly built in .NET Core, the biggest advantage of using the code-first approach is that you can keep your contracts (C# POCO classes) in a separate class library and share the library with the clients through a Nuget package. The library also allows you to convert the contracts to proto files, hence offering portability across frameworks. When you use the protobuf-net.Grpc library, you don’t need to generate proto files manually, and in fact, they are not even generated or used by the library.

One of the key areas where I struggled a little was writing integration tests for gRPC services. With protobuf-net.Grpc, writing integration tests for services is easy. In fact, during a code review, my team did not initially realize that they were reading tests written for a gRPC service because they look incredibly similar to the integration tests for REST services. Even if you decide to use the standard approach of using proto files to define the gRPC contracts, you can use the following procedure for writing integration tests for your service.

Overview

We will build a simple application that returns the list of numbers between two indexes specified in the request. Please download the source code of the sample application from the following repository.

This sample will cover implementing and testing the following two types of RPC (Remote Procedure Call).

- Unary RPC: In this case, the client sends a request to the server and receives a response.

- Server streaming RPC: In this case, the client sends a request to the server and receives a sequence of responses.

Defining The Contracts

Let’s begin with the schema of the request - CountRequest. Since the protobuf serialization depends on the sequence of properties/fields, we must set the property Order denoting the sequence number of the property in the contract.

[DataContract]

public class CountRequest

{

[DataMember(Order = 1)]

public int LowerBound { get; set; }

[DataMember(Order = 2)]

public int UpperBound { get; set; }

}

Next, let’s check out the schema of the response from the server - CountResult.

[DataContract]

public class CountResult

{

[DataMember(Order = 1)]

public int Value { get; set; }

}

The following specification presents how you can define the contract between the client and the server. In gRPC, this interface is defined using the Protobuf protocol syntax. The contract in the following code listing specifies two operations:

- SlowCountAsync: It is a server streaming RPC operation that returns a sequence of

CountResultobjects after successive delays. - FastCount: It is a unary RPC operation that returns the entire sequence of

CountResultobjects to the client in the response.

[ServiceContract(Name = "GrpcSample.LazyCounter")]

public interface ILazyCounterService

{

[OperationContract]

IAsyncEnumerable<CountResult> SlowCountAsync(CountRequest request, CallContext context = default);

[OperationContract]

IEnumerable<CountResult> FastCount(CountRequest request, CallContext context = default);

}

Implementing The Service

After defining the contract, the next action for us is to implement it. Navigate to the class LazyCounterService that implements the service contract that we specified previously.

public class LazyCounterService : ILazyCounterService

{

public async IAsyncEnumerable<CountResult> SlowCountAsync(CountRequest request, CallContext context = default)

{

await foreach (var value in SlowCounter(request.LowerBound, request.UpperBound))

{

yield return new CountResult {Value = value};

}

}

public IEnumerable<CountResult> FastCount(CountRequest request, CallContext context = default)

{

return Enumerable

.Range(request.LowerBound, request.UpperBound - request.LowerBound + 1)

.Select(e => new CountResult {Value = e});

}

private static async IAsyncEnumerable<int> SlowCounter(int lo, int hi)

{

for (var i = lo; i <= hi; i++)

{

await Task.Delay(1000);

yield return i;

}

}

}

The service implementation is easy to comprehend, and so I won’t dwell on the implementation details. Let’s now write integration tests for the two procedures that we implemented.

Writing Integration Tests

I would begin by pointing you to the official Microsoft documentation on writing integration tests in ASP.NET Core. The first step of writing integration tests is to define a Fixture. The fixture contains the common code that is shared between tests. Hence the fixture is an appropriate location to define the TestServer for the integration tests. The following code listing presents the fixture that will aid us in writing tests.

public sealed class TestServerFixture : IDisposable

{

private readonly WebApplicationFactory<Startup> _factory;

public TestServerFixture()

{

_factory = new WebApplicationFactory<Startup>();

var client = _factory.CreateDefaultClient(new ResponseVersionHandler());

GrpcChannel = GrpcChannel.ForAddress(client.BaseAddress, new GrpcChannelOptions

{

HttpClient = client

});

}

public GrpcChannel GrpcChannel { get; }

public void Dispose()

{

_factory.Dispose();

}

private class ResponseVersionHandler : DelegatingHandler

{

protected override async Task<HttpResponseMessage> SendAsync(HttpRequestMessage request,

CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var response = await base.SendAsync(request, cancellationToken);

response.Version = request.Version;

return response;

}

}

}

The one thing in the previous code listing that might have stood out to you is the ResponseVersionHandler class. We need a delegating handler, which handles the response before it reaches the client, to set the HTTP version of the response. Remember that gRPC requires HTTP/2 to function. Due to a known issue with the TestServer, the default version of the response is set to 1.1. Hence, with the delegating handler, we set the version number of the response back to 2.0 (same as the request). You should inspect the integration test code in the grpc-dotnet library for any changes to the guidance.

Finally, navigate to the class LazyCounterServiceShould to find the integration tests for the two methods that we implemented in the service.

public class LazyCounterServiceShould

{

public LazyCounterServiceShould(TestServerFixture testServerFixture)

{

var channel = testServerFixture.GrpcChannel;

_clientService = channel.CreateGrpcService<ILazyCounterService>();

}

private readonly ILazyCounterService _clientService;

[Fact]

public void FastCountFromLowToHigh()

{

// arrange

var request = new CountRequest {LowerBound = 1, UpperBound = 10};

// act

var result = _clientService.FastCount(request, CallContext.Default);

// assert

var resultList = result.ToList();

resultList.ShouldNotBeNull();

resultList.Count().ShouldBe(10);

resultList.First().Value.ShouldBe(1);

resultList.Last().Value.ShouldBe(10);

}

[Fact]

public async Task SlowCountFromLowToHighAsync()

{

// arrange

var counter = 1;

var timer = new Stopwatch();

var request = new CountRequest {LowerBound = 1, UpperBound = 5};

// act

timer.Start();

var result = _clientService.SlowCountAsync(request, CallContext.Default);

// assert

await foreach (var value in result)

{

value.Value.ShouldBe(counter++);

}

timer.Stop();

counter.ShouldBe(6);

timer.Elapsed.ShouldBeGreaterThan(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(5));

}

}

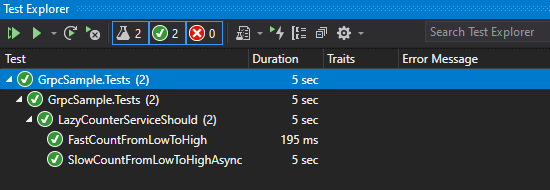

If you have the solution setup in your Visual Studio IDE, run both the tests by typing the shortcode Ctrl+R,A. The following image presents the output generated from the test run.

Conclusion

We discussed the advantages of using protobuf-net.Grpc over the default gRPC implementation in ASP.NET Core. We also discussed how you could write integration tests for your gRPC services. The TestServer is capable of handling HTTP/2 requests (with some caveats), and thus you can write integration tests for gRPC services similarly to how you would write integration tests for a REST service.

Did you enjoy reading this article? I can notify you the next time I publish on this blog... ✍