We all love web badges. You might have spotted many of them in README of repositories, including the repository of my blog, The Cloud Blog. In general, web badges serve two purposes.

- They are visually appealing.

- They display key information instantly.

If you scroll to my website’s footer section, you will find GitHub and Netlify badges that display the status of the latest build and deployment. I use them to quickly check whether everything is fine with the world without navigating to their dashboards. In essence, a badge is an SVG image with dynamic content embedded in it.

Apart from GitHub Actions and Netlify, many other services support generating badges that you can display on a webpage. Let me point you to the popular Shields.io website that you can use to create a custom badge.

Motivation

From the overview of badges, I will segue to an open-source badge I recently created. Visitor counters such as HITS display the number of visitors to a web page and can be embedded in a Markdown or HTML page without adding additional scripts to the web page. I wanted to create a configurable visitor counter that runs on Azure, which supports more configurations and is backed by Azure’s robust services.

Visitor Counter Badge is a simple open-source service you can use to display the number of visitors on a web page, repository, or profile. Every request to render the visitor count badge invokes an HTTP-triggered Azure Function that dynamically generates an SVG image that you can apply on a web page, profile page, or repository.

I plan to develop this service further if there is interest. So, it is essential that you use it, share it, and share your feedback. You can also split the bill of hosting this service with me by making a small donation here.

The Badge

Here is the badge in its default configuration.

Source Code

The following repo is the home of the Visitor Counter Badge. Please create GitHub issues for defects or feature requests. I welcome PRs to make the service better for everyone.

Request Sequences

To use the Function, you first need to register a username and subsequently request a badge. Let’s discuss the interaction between the systems in the two workflows.

Register Username

To use this badge, you first need to register a username. To do that, use an HTTP client of your choice, such as cURL or POSTMAN, to make a POST request to the following endpoint.

curl -X POST -d "" 'https://badge.tcblabs.net/api/hc/[Your Username]'

To store state, I use Azure Table Storage, which is pretty inexpensive and provides high throughput for queries that involve the inbuilt indexes - Partition Key and Row Key.

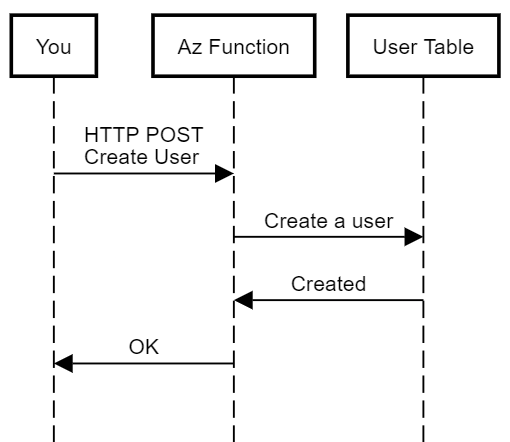

Following is the sequence of the interactions between the systems in the username registration workflow.

Let’s take a look at the code that is responsible for registering the user. The following code in the Function handles the incoming POST request for registering a user.

[FunctionName(FxName)]

public async Task<IActionResult> Run(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get", "post", Route = "hc/{user}/{pageId?}")]

Options options,

string user,

string pageId,

HttpRequest request,

[Table(RecordStore)] CloudTable recordTable,

[Table(UserStore)] CloudTable userTable,

ILogger logger)

{

user = user.ToLowerInvariant();

if (request.Method.Equals("post", StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase))

{

logger.LogInformation("Attempting to register {User}", user);

return await RegisterUser(user, userTable) ? (IActionResult) new OkResult() : new ConflictResult();

}

}

The following is the definition of the RegisterUser method.

private static async Task<bool> RegisterUser(string user, CloudTable userTable)

{

try

{

var operation = TableOperation.Insert(new UserRecord(user));

await userTable.ExecuteAsync(operation);

}

catch (StorageException exception)

when (exception.RequestInformation.HttpStatusCode == (int) HttpStatusCode.Conflict)

{

return false;

}

return true;

}

The method returns either true or false depending on whether the function successfully registered the user or the user’s record conflicted with an existing one.

Fetch The Badge

After the registration, it’s now time to get a shiny badge. A page is uniquely identified through a page identifier (case insensitive) and your username. You can use any unique string to identify your page within your account. The most common choices are the title of the page, a number, or a GUID. Once you select an identifier, you can apply the badge on an HTML page, such as a blog post, using the following code.

<img src="https://badge.tcblabs.net/api/hc/[Your Username]/[Page Identifier]" />

If you want to apply the badge on a markdown file such as README.md or your GitHub profile, use the following code.

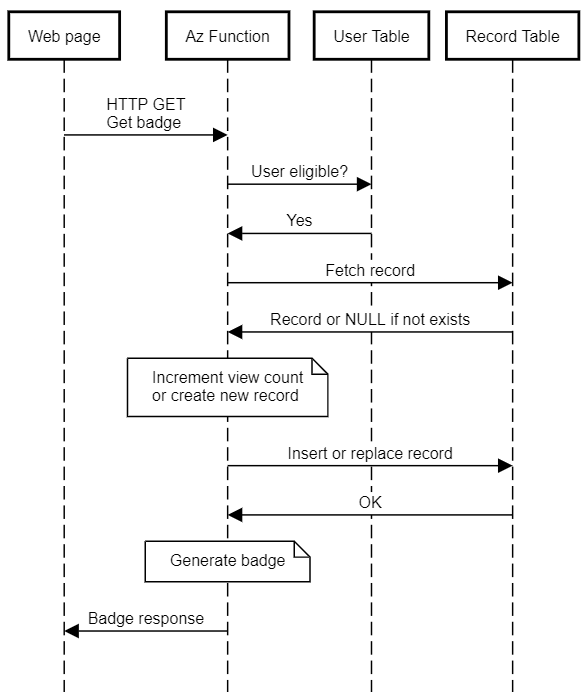

Following is the sequence of the interactions between the systems in the fetch badge workflow.

Let’s take a look at how the Function services the request. Here is the trimmed down version of the Function code that handles the request.

[FunctionName(FxName)]

public async Task<IActionResult> Run(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get", "post", Route = "hc/{user}/{pageId?}")]

Options options,

string user,

string pageId,

HttpRequest request,

[Table(RecordStore)] CloudTable recordTable,

[Table(UserStore)] CloudTable userTable,

ILogger logger)

{

HitRecord record;

user = user.ToLowerInvariant();

pageId = pageId?.ToLowerInvariant().Trim();

if (!await IsUserAllowed(user, userTable))

{

return new UnauthorizedResult();

}

try

{

// Try to avoid concurrency conflicts in a single function host.

await SlimLock.WaitAsync();

// Case insensitive record entity fetch

record = await FetchRecord(recordTable, user, pageId);

if (!options.NoCount)

{

++record.HitCount;

}

// Update record

await UpdateEntity(record, recordTable);

}

finally

{

SlimLock.Release();

}

// Explicitly tell clients to not cache the image.

return NoCacheContentResponse(request, await PrepareImage(record, options));

}

Azure Storage Tables don’t support the atomic increment/fetch-and-add operation. Because of the limitation, multiple concurrent requests for fetching the same badge, which is the combination of username and page identifier, will lead to conflicts when you try to insert an older version of the record. For concurrent requests within a host, I have attempted to mitigate concurrency issues using a SemaphoreSlim lock that will admit up to 100 threads and control concurrency on table reads and writes.

For concurrent requests across hosts, I disabled optimistic concurrency check for entity updates. Without concurrency check, Azure Table Storage will replace the existing record irrespective of its version. The ETag property of Azure Table Storage is used for managing optimistic concurrency. Azure Tips and Tricks website has a nice writeup on the purpose of the ETag property. The following is the definition of the UpdateEntity method.

private static async Task UpdateEntity(ITableEntity record, CloudTable cloudTable)

{

record.ETag = "*";

var operation = TableOperation.InsertOrReplace(record);

await cloudTable.ExecuteAsync(operation);

}

Finally, after updating the hit count, the Function returns an SVG image to the client. One key obstacle in serving the image to the client is caching. If you add images to GitHub, it will use Camo to anonymize the images and cache them. To force the client (including GitHub) to fetch the badge on every request, we will add caching headers to the response asking the client not to cache the response. The NoCacheContentResponse method adds the relevant headers to the response as follows.

private static IActionResult NoCacheContentResponse(HttpRequest request, string preparedImage)

{

request.HttpContext.Response.Headers.Add("cache-control", "no-cache, no-store, must-revalidate, max-age=0");

return new ContentResult

{

Content = preparedImage,

ContentType = ResponseType,

StatusCode = (int) HttpStatusCode.OK

};

}

The SVG template image stored in the application has several placeholder strings substituted with relevant values to prepare the final image sent in the response. The method PrepareImage is responsible for preparing the final image from the template as follows.

private static async Task<string> PrepareImage(HitRecord record, Options options)

{

_imageString ??= await GetImageFromResource(ImageFile);

var imageSb = new StringBuilder(_imageString);

imageSb.Replace("@Count", FormatCount(record.HitCount, options));

imageSb.Replace("@EyeBg", options.IconBackgroundColorCode);

imageSb.Replace("@TextBg", options.TextBackgroundColorCode);

imageSb.Replace("@EyeColor", options.EyeColorCode);

imageSb.Replace("@TextColor", options.TextColorCode);

return imageSb.ToString();

}

As you can see, there are several placeholder strings available in the template. The configuration values are read from the query string of the HTTP request, and they affect the look and feel of the badge and its behavior. You can examine the supported configuration parameters and their examples in the README of the repository.

Finally, you can host the Azure Function and the supporting infrastructure to your Azure subscription using the Azure Resource Manager (ARM) template available in the repository. The ARM deployment button in the README file of the repository makes this process a breeze. I hope that you will give this badge a try. I look forward to your feedback.

Did you enjoy reading this article? I can notify you the next time I publish on this blog... ✍